Sarah brings in her energetic seven month old Italian Spinone, Flo, to see Professor Noel Fitzpatrick after scans reveal she has a hole in her shoulder joint. She is in significant pain due to the missing cartilage exposing raw bone and joint fluid getting into the hole. Sarah brings Flo to Professor Noel Fitzpatrick in the hope that a solution can be found for this very young dog.

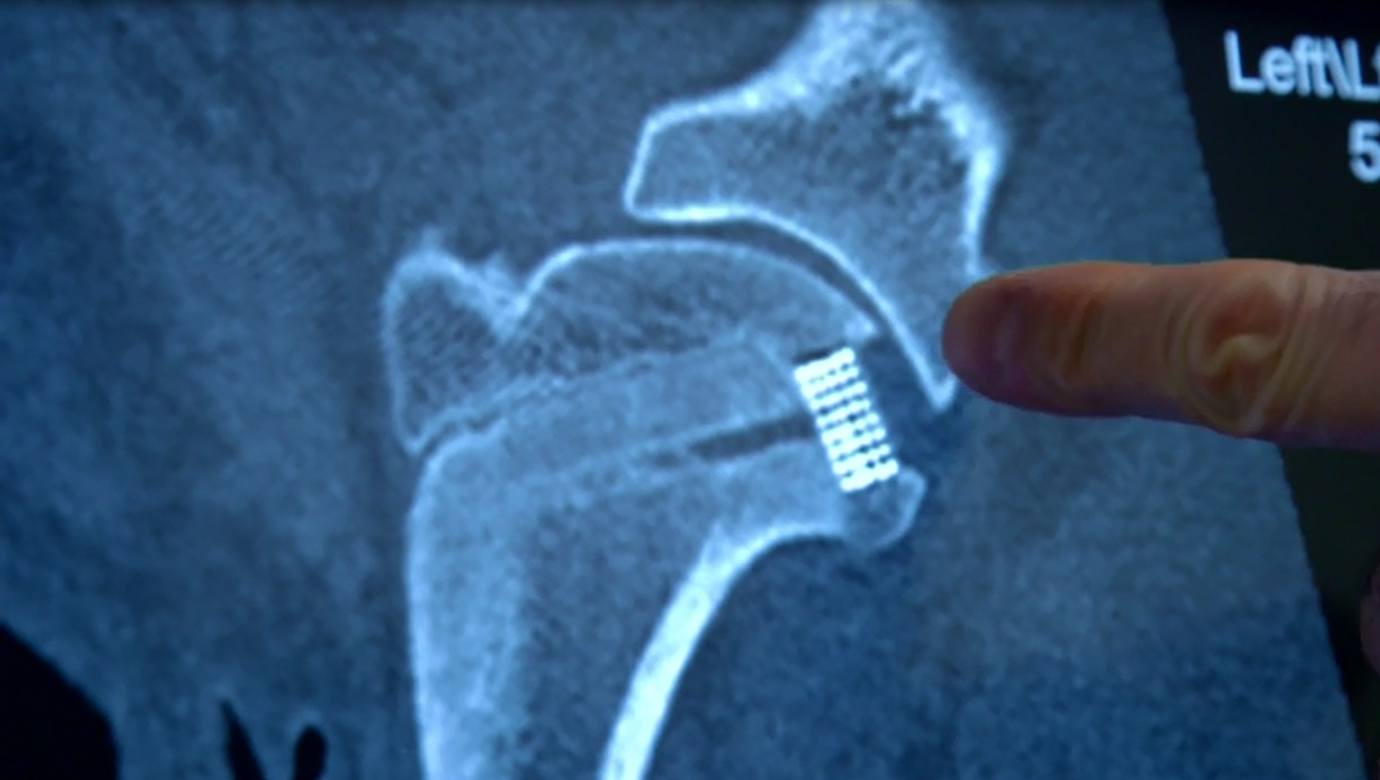

Noel performed x-ray, CT and MRI imaging as well as an arthroscopy to see inside the joint. These tests confirmed a large and deep lesion called Osteochondrosis Dissecans (OCD) affecting the joint surface of the head of the main arm bone (humerus). OCD is a developmental condition that arises due to a disturbance in the normal differentiation of cartilage cells resulting in failure of endochondral ossification. Normally the layer of cartilage at the end of a bone turns into solid bone during growth, leaving a thin coating on the joint as a dog grows. In dogs that grow very quickly, the rapid cartilage growth can outstrip its own blood supply causing abnormal cartilage development, which results in it flaking off into the joint with lameness, pain and subsequent osteoarthritis.

Historically Flo’s condition would have been treated by taking out the flaking cartilage and hoping for the best with a scar growing into the crater left behind. More recently Noel was the first surgeon in the world to help develop a synthetic filler for such defects, but the Holy Grail would be to grow a new joint surface that might be made of the same cartilage cells that would have been there in the first place. So, with regenerative medicine opening up new horizons, Noel offered Sarah a custom-made implant to exactly fill the hole in Flo’s joint, which would then be packed full of cells harvested from Flo’s own tissue to encourage the implant to fully integrate with the bone, and to create a new cartilage joint surface. It’s a revolutionary technique that Noel is the first ever surgeon in the world to attempt in a clinical patient, but Sarah was willing to seize the opportunity of giving Flo the best possible chance of a normal pain-free life; putting her faith in Noel – and in biology.

The custom-designed implant was delivered 10-days later and consisted of a disc of porous titanium metal that was similar to the honeycomb structure of bone. This was topped by a carpet-like layer of woven fabric containing polylactide, a climbing frame for cartilage cells. The polylactide was seeded with stem cells derived from Flo’s own cartilage cells, meaning that they were intended to grow into cartilage exactly the same as that which should have been there in the first place (hyaline cartilage). To embed the implant, Noel drilled the hole in Flo’s shoulder deeper to receive the double-layered device. Noel then injected more stem cells and a glue called fibrin around the implant, hoping that over 12 weeks the cells would form a new cartilage joint surface.

Flo recovered well from the surgery under the watchful eye of Noel and his team and was sent home to Sarah and her family just two days later.

12 weeks on, Flo was admitted to the practice for a repeat arthroscopy to check on the progress of implant integration. Noel was delighted with what he saw. Not only was Flo doing remarkably well functionally and walking without lameness, but there was clear evidence that satisfactory integration of the implant had occurred in the joint surface. Flo has since returned to a normal life, bouncing around as a young boisterous puppy ought to do!

This is a remarkable example of how regenerative medicine heralds a new era of advanced treatments which could simultaneously benefit both animals and humans. Find out more about the charity Noel has founded to promote One Medicine: www.humanimaltrust.org.uk